- Home

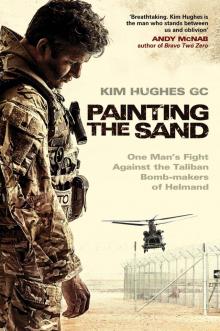

- Kim Hughes GC

Painting the Sand

Painting the Sand Read online

For Mum

Contents

Foreword

1 First Op – Boots on the Ground

2 Man Down

3 Leaving

4 How Did I Get Here?

5 Bomb School

6 First Bomb

7 The Science of Explosives – the Layman’s Version

8 Keeping Score

9 God Complex

10 Where the Fuck’s the Bomb?

11 Losing a Mate

12 Blown Up

13 R & R

14 Sangin – Death in the Wadi

15 Painting the Sand

16 Aftermath

17 Pharmacy Road

18 The Fallen

19 Chocolate Fireguards

20 Boredom and Bullshit

21 They Want to Kill Me

22 Last Job?

23 Is that a Fucking Rubber Dinghy?

24 Pissing off Politicians

25 Going Home

Epilogue

Appendix

Glossary

List of Illustrations

Foreword

Improvised explosive device – IED – the preferred weapon of terrorist groups around the world for over forty years. The IED can kill you two ways. A big bomb, say twenty-plus kilos, will blow you to pieces. Quick and painless. But if you’re unlucky, I mean really unlucky, the blast will cut you in half, take away your legs and leave you disembowelled. You might survive but not for long, not unless you’ve got immediate access to a fully equipped trauma hospital with highly qualified battle-hardened war surgeons.

In Afghanistan in 2008, the Taliban began making IEDs by the thousand. The bombs weren’t sophisticated – in fact the quality was crap. But that wasn’t the issue. The problem was the number. By 2009 there were an estimated 10,000 IEDs buried in the ground in Helmand at any one time. British soldiers were being killed and injured every day. Morale was low and for a few brief months over that summer the Taliban were winning.

The best weapon against the IED is the bomb disposal operator. That was my job. When I flew into Helmand on the 6 April 2009 I was expected to hit the ground running, to tackle everything the Taliban could throw at me. I thought I was ready but, in reality, I wasn’t.

A couple of decades earlier when the Troubles in Northern Ireland were at their height a bomb disposal operator could be expected to deal with six to eight complex bombs in six months and in the busier parts of the province sometimes a lot more. By the end of my six months in Helmand I had defused more than a hundred IEDs.

What you will read over the next few hundred pages will tell you how I and my team helped beat the Taliban and lived to tell the tale. It was often a close-run thing. We made mistakes, casualties were taken, but in the end we were lucky. It’s a tough read. I haven’t pulled any punches. The book has been written so that you will know what it’s like to get up close and personal to an IED. How an IED is put together and what it’s like to defuse a bomb in a minefield when you’re surrounded by the dead and the dying.

Today, right now, in towns and cities across the UK would-be terrorists are designing a new generation of IEDs – more deadly than anything seen in Afghanistan. It’s a game of cat and mouse and at the moment we’re ahead, but for how long?

1

First Op – Boots on the Ground

13 May 2009

Ten minutes to landing. Thank fuck. The longer we were airborne, the greater the risk. The Chinook was an easy target, even at night and the Taliban were gunning for a big prize. Burning alive in Afghan wasn’t the way I wanted to sign off.

My arse was aching like you wouldn’t believe and my legs felt like they belonged to someone else. My body was screaming with cramp and the heat was unbelievable. I was sitting down on the Chinook’s shiny, steel deck, unable to move, straitjacketed by my own equipment. My body armour, great for stopping bullets, acted like a thermal blanket, leaving me soaked in sweat and panting for breath. I shit you not, it was like a fucking sauna.

It didn’t worry me that we might be landing straight into the middle of a Taliban ambush. We’d been warned that the landing zone might be hot. Casualties were expected, the risks were high. Fine. Just get me on the ground and off the fucking chopper.

Strapped to my chest was my SIG 9mm pistol and a load of explosive ordnance disposal (EOD) kit. Ammo pouches on my hips held at least six mags of thirty rounds – in Afghan everyone had to be ready to fight. In one hand I held my rifle – the 5.56mm SA80 – a weapon with a bad reputation, but by 2009 effectively it had been rebuilt and was pretty decent. In the other hand was my day-sack, containing everything I needed to defuse IEDs.

The Chinook had been stripped of all its seats so more soldiers could be crammed in. Forty of us were squeezed inside an aircraft designed to carry half that number. That’s forty fully equipped troops carrying rucksacks and weapons, all sitting or squatting, unable to move. I would have happily paid a grand for a few more inches of legroom.

The engines screamed with the demands of flying at low level, hugging valleys, using the natural cover of the barren Helmand desert. I closed my eyes hoping to doze but something began pushing against my leg. ‘Jesus, give it a rest,’ I groaned. I reached forward ready to lash out, expecting an arm or leg but instead grabbed a handful of fur.

It was the explosive search dog sniffing at my kit. The dog’s senses had gone crazy – my day-sack was full of explosives. I gently stroked its fur and felt his panting breath on my hand. It must have been suffering far more than me but the dog lay quietly without complaint. Thoughts of my own dog, a hyperactive young cocker spaniel began to fill my mind. I called him Sabot, after a piece of ammunition – what do you expect from an EOD soldier? I was gently transported to happier times, playing fetch, going for long wintry walks, Sabot at my side.

‘Five minutes,’ the RAF loadmaster signalled.

The Chinook had been airborne for about fifty minutes and the smell of aviation fuel was starting to make everyone feel nauseous. An acrid stench of fresh vomit began to waft through the chopper and I started to gag; there are only a few things in this world that make me want to throw up and that smell is one of them.

A young soldier, still a teenager, was retching violently. Tears were streaming down his face as he struggled for breath. We were all scared – none of us knew what the future held.

His section commander leaned over – anger in his eyes – mouthing the words: ‘Get a fucking grip.’

‘One minute,’ the loadmaster shouted holding up a solitary finger for those who couldn’t hear.

I tried to stand but my legs, numbed into paralysis by sitting cross-legged, buckled and I collapsed in a heap. A hand reached down from above helping me to my feet.

‘Cheers, pal,’ I said but my words were lost beneath the deafening roar of the engines.

The helo had barely touched down before the loadie started screaming for everyone to get off. A stationary chopper in Taliban territory was a sitting duck. I charged into the dark void, soldiers around me stumbled and fell. Chaos.

I ran clear and fell on my belt buckle. The ground was unexpectedly wet with dew and smelt clean and fresh – not what I was expecting. I looked up to scan the ground ahead and felt my helmet hanging half off my head as though I was a recruit in the first week of training. A basic error. I’d spent the last two days squaring my kit away for the operation and I’d forgotten about my helmet. Hours had been spent getting my kit sorted, making sure everything was where it should have been. Personalising my body armour to make sure it fitted comfortably, giving me easy access to my tools and pistol. It was amazing how many hours could be whiled away ensuring that everything worked and was comfortable. A little bit of OCD went a long way in Afghan.

&

nbsp; In Helmand your kit was your life-support system. Body armour, pistol, helmet, field dressing, tourniquet (in case you lose a leg or two), morphine, to dull the pain of a traumatic amputation, wire snippers, smoke grenades, and the all-important paintbrush, used for clearing the sand away from the IEDs. I kept my 9mm SIG pistol within easy reach – it was my close protection weapon. But if I had to use it in anger then something had gone seriously wrong.

I also had another 50 kilograms of kit that I squeezed into my Bergen rucksack and that was meant to be ‘light scales’, meaning you took what you could carry, nothing more. I didn’t have the luxury of a bomb disposal suit – a 50-kilogram Kevlar padded jacket and trousers combo with ballistic plate designed to allow the person inside to, within reason, survive a blast. I couldn’t run in it and so the suit was about as tactically sound as a Day-Glo vest – no use in Afghan.

Fuck up over here and it’s game over. What’s left of me gets mopped up and flown home in a box and I become just another sorry stat on an ever-growing casualty list. A brief mention on the news, grieving parents, tears, friends talking of a brave soldier who gave his life for his country. A few minutes of useless fame before the next pissed-up celebrity steals the headlines.

Not the end I had in mind. This was my first mission in Afghan and I wanted to do well. I wanted to be the operator who can be relied upon – not some idiot that turned himself to red mist first time out. I’d come too far, worked too hard and sacrificed too much for it to all end on day one.

I was in charge of a Counter-IED team on Operation Herrick 10 – the code name for the war in Afghanistan. The main headquarters was Camp Bastion, a vast tented city in the middle of Helmand that acted as a central hub for British and NATO forces. It grew in size every day; at any one time several thousand troops would arrive, preparing to leave or waiting to go into battle. The place was almost self-sustaining, producing its own water and getting rid of its own waste. There was a hospital, complete with trauma team and Intensive Care Unit, dining halls churning out thousands of meals a day, gyms, coffee shops, a NAAFI with satellite TV and a Pizza Hut. It all helped to remind us there was life beyond the shit-filled ditches of Helmand. Bastion also had an airport, which had it been in England would have been almost as busy as Luton. There were even traffic police to ensure that troops stuck to the camp speed limit of 15mph. That was life inside the wire. But out in the badlands of Helmand life was a little different.

Inside our cavernous, white air-conditioned tent in Bastion talk was absent. The piss-taking, jokes and banter that filled idle minutes had been replaced by focused silence. It was kit-check time. Check, check and check again. The packing and reorganising was partly out of necessity and partly to keep our minds occupied, a way of wasting a few hours in between eating, trying to sleep and reading. Soldiers throughout the centuries have done the same, attempting to control their nervous anticipation as they waited to go into battle.

My No. 2 and second-in-command Corporal Lewis Mackafee, was keen to get out. One thing he wanted was a firefight with the enemy. Secretly we all did. We all wanted to say that we’d been in contact but you needed to be careful what you wish for, especially in Afghan.

The Electronic Counter Measures (ECM) Operator, Lance Corporal Dave Thomas, was very bright, but quiet, and always on top of his kit, making sure it was clean and in good order. His equipment was top secret, or at least how it worked was. It was designed to jam radio frequencies so the Taliban couldn’t target us with remote-controlled (RC) IEDs.

The search team, the other part of my unit, had trained together for over a year and had grown as close as brothers. The search commander was Corporal Alan Chapman, a gleaming soldier and a born leader. His team looked up to him, especially the younger lads who were barely out of their teens: Matt, Malley, Harry, Sam and Robbo, who were bright lads with great attitude, the requirements for a High Threat Search Team. Most of their mates were probably at uni or back home in the pub cheering on their favourite football team.

Dust as fine and soft as talcum powder blanketed everything inside Bastion. Tents, vehicles, aircraft, the gym, even the toilets, nothing was spared. But you learned to deal with it. Someone once said the dust is mainly composed of centuries of human shit dried by the desert heat and turned to dust by the desert winds. Now the British Army were sucking it up, fighting a war that was never meant to happen against an enemy who had no concept of defeat. Some of the people we were fighting had been at war longer than most of us had been alive. The Taliban might be poorly educated, ill-equipped and out-gunned but they were committed and loved nothing more than a good dust-up.

Brimstone 42 – the call sign of my Counter-IED team – were itching for action. I know that sounds like a cliché but it was the truth. We were squared away and swept up. Now we wanted to test ourselves, take on the Taliban and pull bombs out of the ground. We wanted to save lives and win our war. Like every soldier arriving in Helmand, my guys had been trained and tested to within an inch of their lives. In theory there was nothing more we could learn. Each one of us knew everything there was to know about our trade – the only thing we lacked was experience.

‘If you remember one thing remember this: in Afghan what can go wrong will go wrong,’ one of the instructors said to my team on the last day of Role Specific Training (RST) three days earlier. That simple statement played over and over in my head. It became my own personal mantra. In Afghan what can go wrong will go wrong, so plan accordingly.

Soldiers died there every day because they either messed up, became complacent or were just unlucky – two out of three were in their control. That was the reality and the quicker you learned that the better. The best you can hope for at the end of six months is to be alive – preferably with both arms, legs and your bollocks intact. Anything beyond that is a bonus.

The Chinook that had dropped us lifted into the night sky creating an instant brown-out as dust and crap was kicked up into a mini whirlwind by the downdraught of its rotor blades. I buried my face in the damp desert and waited for a few seconds before clambering to my feet. As I lowered my night vision goggles (NVGs) night became day and it became apparent I was not alone. The night was lit up by the bright infrared beacons mounted on the side of the soldiers’ helmets, which were used to help aircraft, helicopter gunships and ground troops to identify friendly forces. A scene of utter chaos began to unfold around me. Hundreds of soldiers were spread across the fields, seemingly without anyone in control. Chinooks were landing every few seconds disgorging an army of troops. It was day one of Operation Sarack – a battlegroup search-led operation into a Taliban-held area of Helmand.

Two large compounds – basically farms – had been identified as potential IED-making factories. The production of the bombs had become a cottage industry; hundreds, possibly thousands, were being made and they were having a devastating impact on the war. ‘Improvised’ meant they were constructed from almost any materials – the Taliban could make a bomb out of two pieces of wood, hacksaw blades, some wire, a Christmas tree light and about 10kg of home-made explosives, the main charge. A 20kg main charge will blow you to pieces, anything bigger and a mop will be needed to deal with what’s left.

The plan was to swamp and secure the area with troops, seal off the compounds, clear any Afghans, either willingly or otherwise, and then conduct a detailed search. Anything that looked like IED would be handed over to my Brimstone team to deal with.

Senior officers will spend days, sometimes weeks, planning military operations. Orders sessions can last several hours as the information distils down from the top brass to the soldiers on the ground. It is a massively time-consuming process where every eventuality is planned for. But as every soldier knows no plan survives contact with the enemy.

Almost immediately, the mission, at least my team’s part in it, began to unravel. Initially two Brimstone teams were supposed to deploy on the operation but twenty minutes into the briefing that was cut to one. Then, just as we were about to b

oard the helicopters, I was told that our objective had now changed. Again not a massive issue as the fundamentals of the operation remained: get to the objective and clear it – simple.

All Counter-IED teams carry the prefix ‘Brimstone’ as part of their radio call sign and my team consisted of eleven soldiers: a four-man bomb disposal team – that’s me, my No.2, an Electronic Counter Measures (ECM) Operator and my infantry escort to watch my back while I was dealing with the bomb. I was also supported by a Royal Engineer Search Advisor (RESA) and a Royal Engineer Search Team (REST), which consisted of six, very bright and ridiculously brave soldiers. They found the bombs for me to deal with. Brimstone 42 was part of the Counter-IED Task Force, a special unit created to tackle the increased number of IEDs.

The last-minute objective change meant my team were split across two helos, so they were God knows where on the battlefield when we hit the landing zone. After a few minutes of scouring the landing zone I spotted my No.2, Lewis, heading towards me. Following behind were Dave, the ECM Operator and my infantry escort. It was good to see them. I could deal with changes to the plan but if we had been split up we would have been no use to anyone.

I dropped to one knee in the middle of a field as the team came together. ‘All right, lads? Everyone OK?’ I whispered. They nodded but no one spoke. ‘We’re moving off to north, that way. The sun is coming up on our right to the east. We’ve got about a K [kilometre] of tabbing to the objective.’

If the fighting had kicked off at that moment we’d have been in serious trouble. The ground was boggy. Mud clung to my boots. Trying to run, weighed down by kit, would have been impossible. No one had mentioned that in the briefings. The fetid smell of human shit hung heavily in the air, an indication that habitation was close by, and the night was sticky and warm. I was drenched with sweat and beginning to dehydrate. Above were bats feasting on mosquitoes dive-bombing the line of troops stretched out into the darkness. I looked up at the night sky. There was no light pollution and I gazed in awe at the vastness and clarity of the Milky Way, twinkling light years away above me. I was oddly comforted in the knowledge that it was the same sky I could see from my home in England and I found myself smiling at its beauty.

Painting the Sand

Painting the Sand